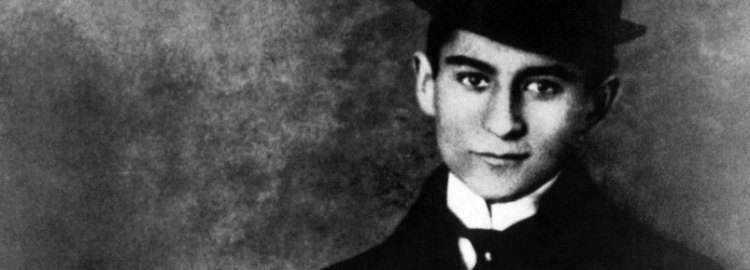

I’m still trying to sort out Franz Kafka. He was the topic of this semester’s independent literature study–my second-to-last in the on-going project with the enigmatic German Professor, which began three semesters ago with Thomas Mann and Robert Musil. It’s the best thing I’ve done as a student here, this intensely personal investigation of tortuous novels that has expanded to include music, philosophy, aesthetics, and myth.

Franz Kafka is such a different figure than Mann or Musil. His obsessions are different, as are his questions and his solutions. His world is entirely opposed to Thomas Mann’s, all secular humanism and sparkling irony and the brilliant residue of 3,000 years of art–opposed, too, to Musil’s intensely private universe, where the glance shared between two people occupies a dozen pages of metaphor-laden prose. If Mann addresses the relationship between man and his intellectual heritage, and Musil the relationship between man and himself, then Kafka addresses the relationship between man and God. His spirituality is real and aching and, and Camus writes, the questions he poses are those of a soul in quest of its grace. What do we do when we are confronted with the Other-worldly? Is God cruel and absurd, or full of goodness? Can human wisdom and strength win a way to the Divine? Certainly, one can read Kafka as a critique of modern bureaucracy, the industrialization of mankind, etc. etc.–but to me it is the religious nature of his works that transcends.

~~~~~~

Leaving philosophy aside, what about the writing itself? To me, perhaps the most pressingly disturbing aspect of Kafka’s prose was its lack of a Bezugsrahmen–a frame of reference or allusion, an overt dialogue between the author and the art and thought of the past three millennia. Kafka’s world exists apparently in a vacuum, in a universe of isolation that is as cultural and intellectual as it is personal. His characters don’t hang pictures from Dürer or Caspar David Friedrich on their walls; they don’t read books by Schopenhauer or Plato. There are no direct references in the novels (Schloss, Prozess) to Shakespeare or to Nietzsche or Antiquity–as readers, we are hardly aware that such things exist. If there is a dialogue between Kafka’s figures and their intellectual forebears, it is hidden.

This utter lack of reference to a greater intellectual tradition is especially unsettling to me, because I revel in The Dialogue, locate great spiritual and intellectual meaning in my ability to connect to three thousand years of thought. To have these connections ripped out from under my feet is intensely disorienting. How different, again, from Thomas Mann! His books are dialogues in essence–long, heady, sometimes tortuous conversations between the ideas and worldviews and artworks of human civilization. And as a result, none of his figures are ever truly isolated. Certainly, they are sometimes despairing, desperate, lonely. In spite of it all, though, they always partake of and above all believe in an intellectual and artistic tradition that is greater than any individual–a tradition that offers, I think, a sort of transcendence, a consolation.

In Kafka there is no such consolation. There is none of Coriolanus’ there is a world elsewhere, no sense that Kafka’s figures can find redemption by situating their own struggles within a philosophical or aesthetic framework that has existed for millennia and will carry on after they are gone. Joseph stands before the court in The Trial and never thinks, “Ah, so it was with Socrates in Athens. I understand now; this is what I am to do.” K. fights unceasingly to gain entrance in the castle, but he does so without the great dictum of Goethe’s Faust: Wer immer strebend sich bemüht, den können wir erlösen. Whoever strives with all his might–that man can we redeem. He remains isolated, intellectually as well as physically.

But in the end, isn’t this lack of a Bezugsrahmen infinitely fitting to Kafka’s universe? The lack of a Dialogue, the emptiness, the intellectual silence all serve to emphasize aloneness of the characters. Their hermetic solitude is perhaps the tragedy of the novels.

~~~~~~

Kafka’s world is also disturbingly free of humanism. Humanism tells us that men and women can move forward on their own strength, can become wiser and better and more farsighted in ways that accomplish things, in ways that lead to creation or beauty or salvation. Kafka takes these ideas and turns them upside down.

He does this above all in Before the Law, the page-long parable at the end of The Trial. In the story, a nameless man seeks in vain to gain access to the Law (grace, God, heaven?). There are a series of gates in his way, and a door-warden who rebuffs all of his attempts to enter even the first. The man sometimes sees a gleam of light through the passageway beyond the door, but dies at the end of the story without ever having set foot inside.

The story, I believe, is fundamentally a-humanistic. The seeker doesn’t become stronger through all his questioning, striving, learning, believing–but rather the opposite.

Kafka becomes anti-Goethe. Whoever strives with all his might–that man dies of exhaustion.

In this light, perhaps the most tragic sentence in the novels is the door-warden’s final statement to the man, in his last moments of life: “Der Eingang war nur für dich bestimmt. Ich gehe jetzt und schließe ihn.” The entrance was only meant for you. I am going now and closing it. That is our torture, our tragedy–that we are wise enough to know such an entrance exists, and wise enough to seek it with all our strength–but too limited, physically and spiritually, to ever gain entrance on our own strength. Humanity finds itself in an impossible position.

In this way, I think, Kafka’s is a world that the ancient Greeks would have recognized–where human beings are fundamentally weak, where their limitations are at the forefront of human existence. The divine realm exists, sends messengers, is tangible and present–but is ultimately careless and inscrutable.

~~~~~~

There is one more thing about Kafka’s characters, however, at the end of it all: wherever they are, in whatever circumstances, despite all confusion and weakness–they are always going to a window and opening it, and looking out. I like to imagine that this throwing-open of windows, repeated again and again throughout the novels, is itself a sort of human victory. It doesn’t matter that the world beyond the windows is often dark and snow-filled. It’s the action that counts.

~~~~~~

If I had finished this post five days ago, I would have ended it there. Kafka’s books are superb because they are so unbearably, unflinchingly bleak. Reading him is fascinating and compelling and cathartic in the same way reading Greek tragedy is, because we are presented with a world in which there is no out. A few open windows, a gleam of light through a impenetrable gate–what’s that, really? The works end with human limitation writ large.

Now, however, I’m entrenched in Søren Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling, and it’s throwing all of Kafka into a very new light.

Per Kierkegaard, Kafka is drawing our attention not to human weakness, but to mankind’s incredible, defiant potential for perseverance, for real and tangible hope. His characters are the greatest of heroes because they are heroes of faith. They have looked into the absurd and comprehended the paradox and have chosen to believe.

But that’s all still half-formed, still confused in my own mind. There will be more to come later. In the end, Kafka is the sort of author who shifts over time–and that, I think, is why we read him.